The Cat Behind the Hat

In 1957, Dr. Seuss, revolutionized the way that generations of children would learn to read. In the nearly 60 years “since The Cat in the Hat exploded onto the children’s book scene, Theodor Seuss Geisel has become a central character in the American literary mythology, sharing the pantheon with the likes of Mark Twain and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Of his many imaginative stories, The Cat in the Hat remains the most iconic.” (U.S. News & World Report August 13, 2007)

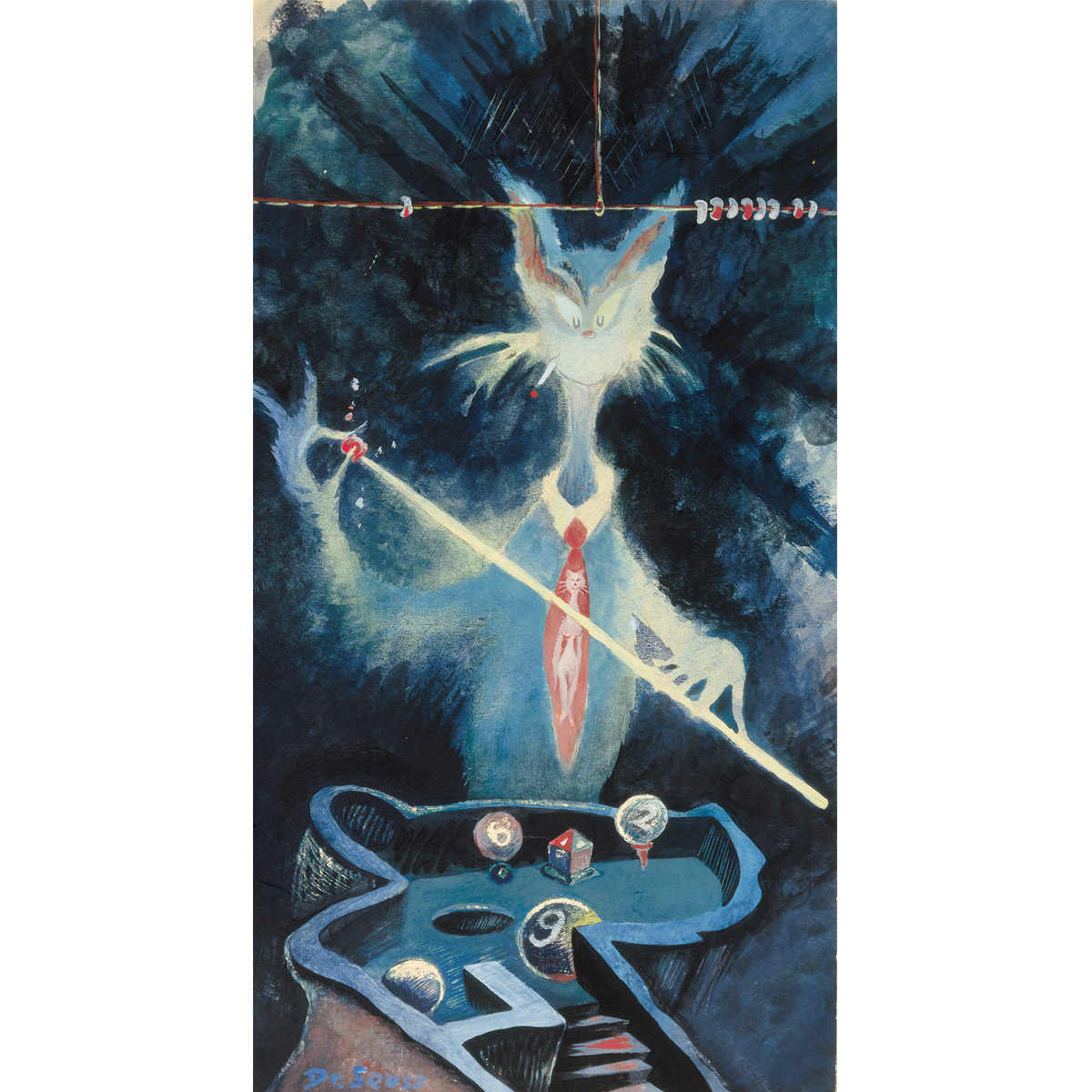

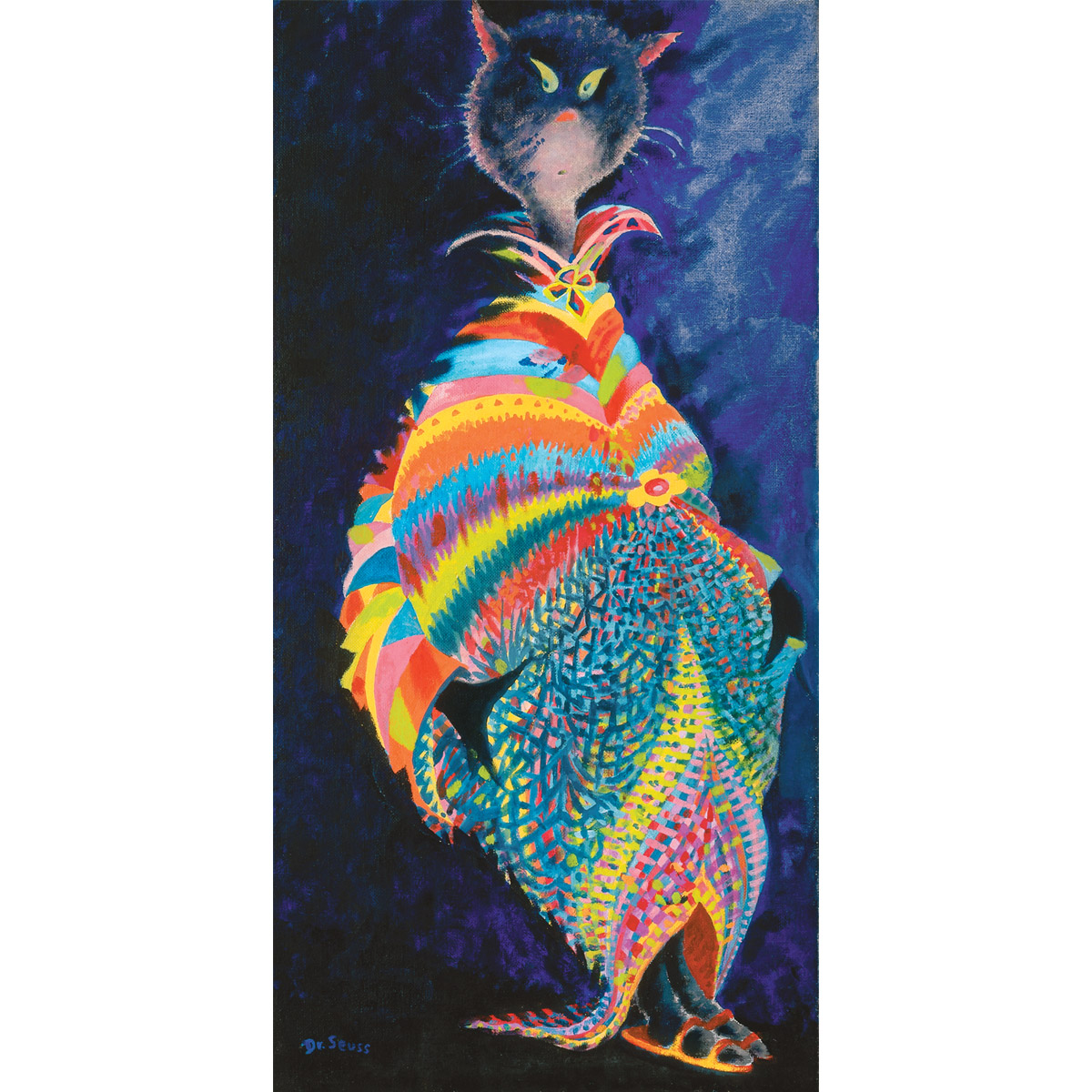

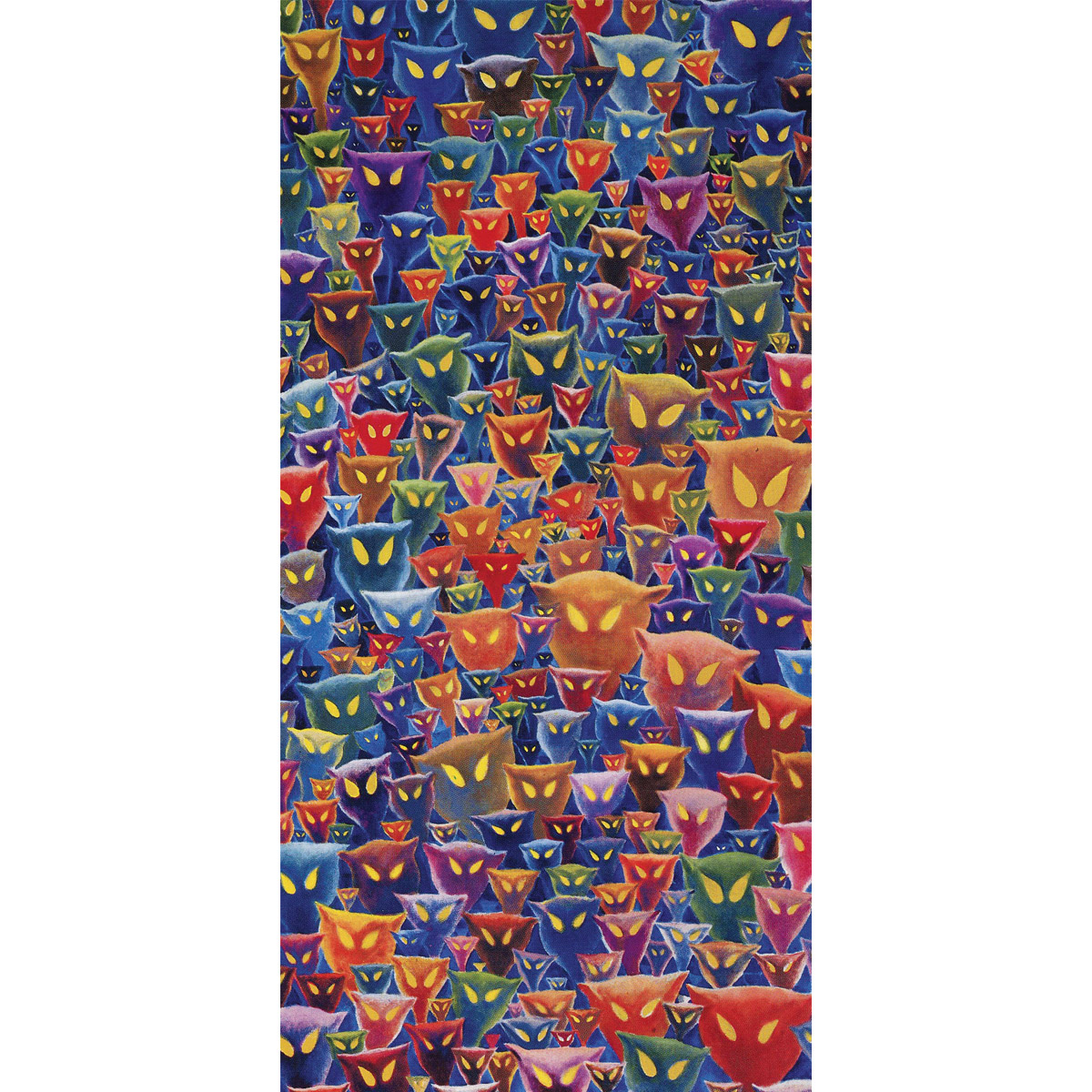

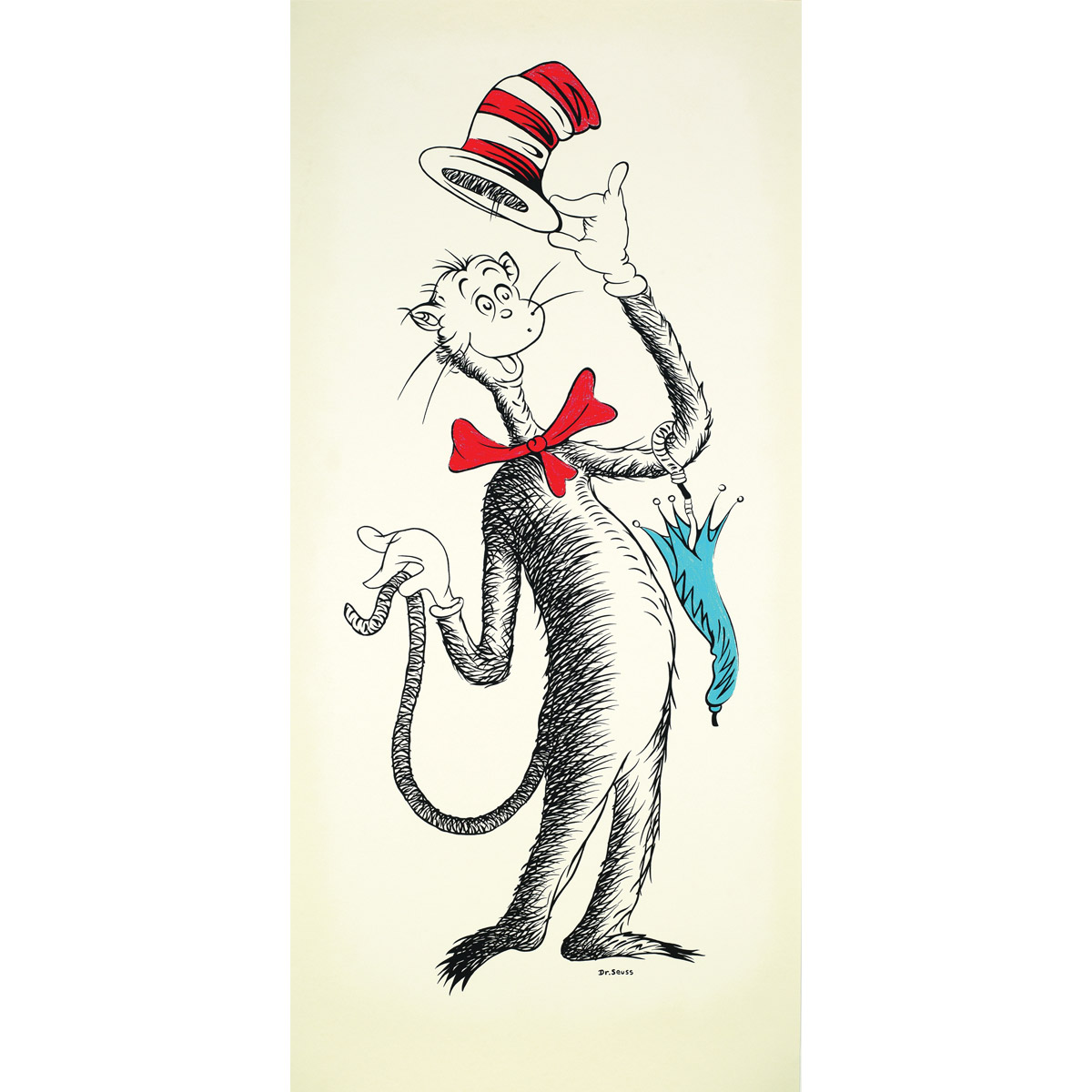

Over time The Cat in the Hat became more than a recurring character for Ted; it also morphed into his alter ego, surfacing repeatedly in his surrealist thematic cat paintings. Whether he was a Surly Cat being ejected by an Edvard Munchian screamer, a member of the Pinkish and Greenish iconic twosome dispensing a magic dose of mischief, the Clouseauian inspector sleuthing a felon, or the Green Cat with Lights attributed to fool unsuspecting friends, Ted’s intentions went far deeper. Disguised as a potpourri of nonsense, these works combined his vivid imagination with a thoughtful understanding of human nature. Truths are whispered from these playful paintings and, if examined closely, one can see Ted winking from every whiskered face.

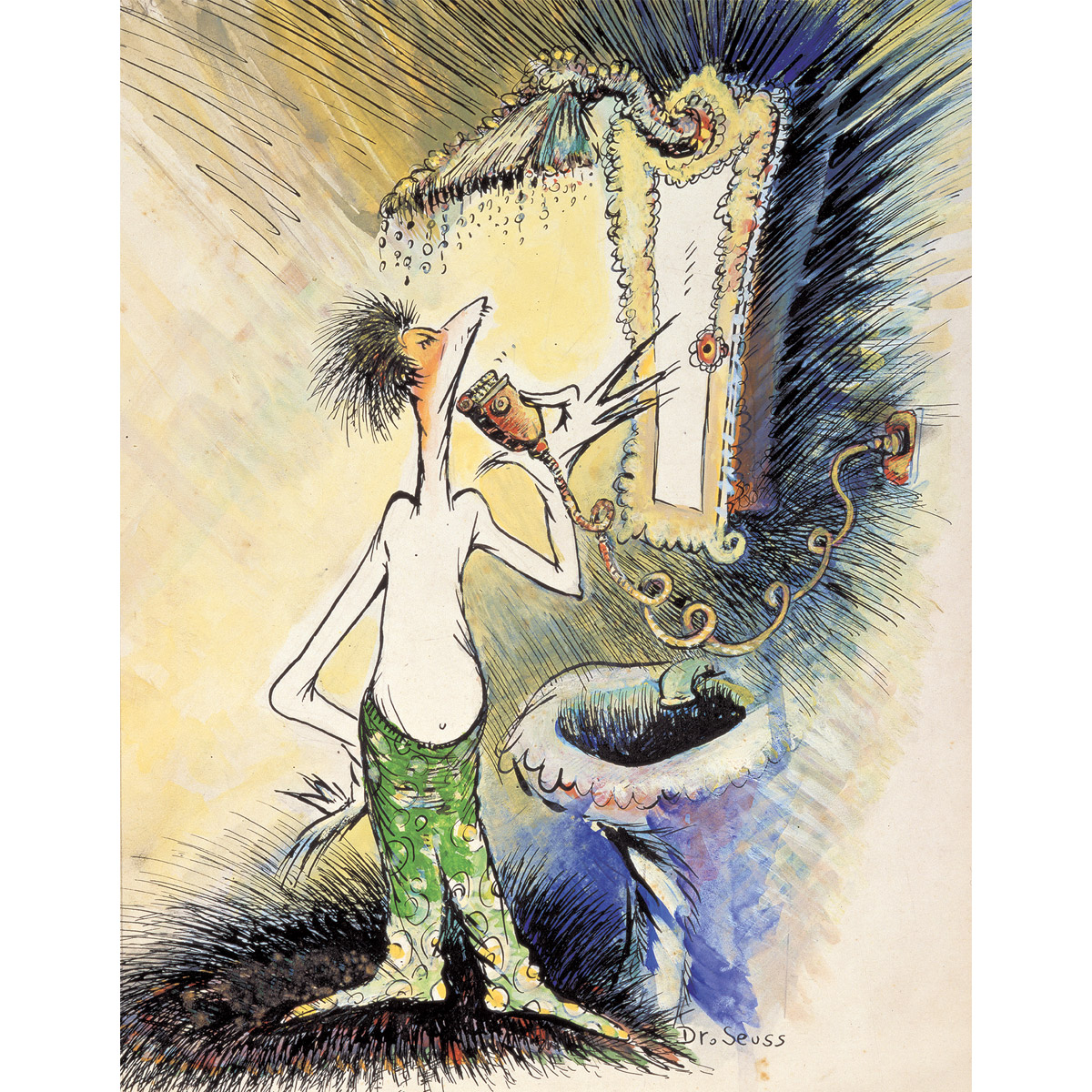

Self-Portraits

Self-portraits are rare and highly prized portrayals that reveal a unique inner vision that only the artist can provide. Theodor Seuss Geisel painted merely a few self-portraits during his lifetime, each of which presents an entirely different examination of who “Dr. Seuss” was and is.

The portraits included here are: Self-Portrait of an Artist Worrying about His Next Book, Self-Portrait as a Young Man Shaving, and The Cat Behind the Hat

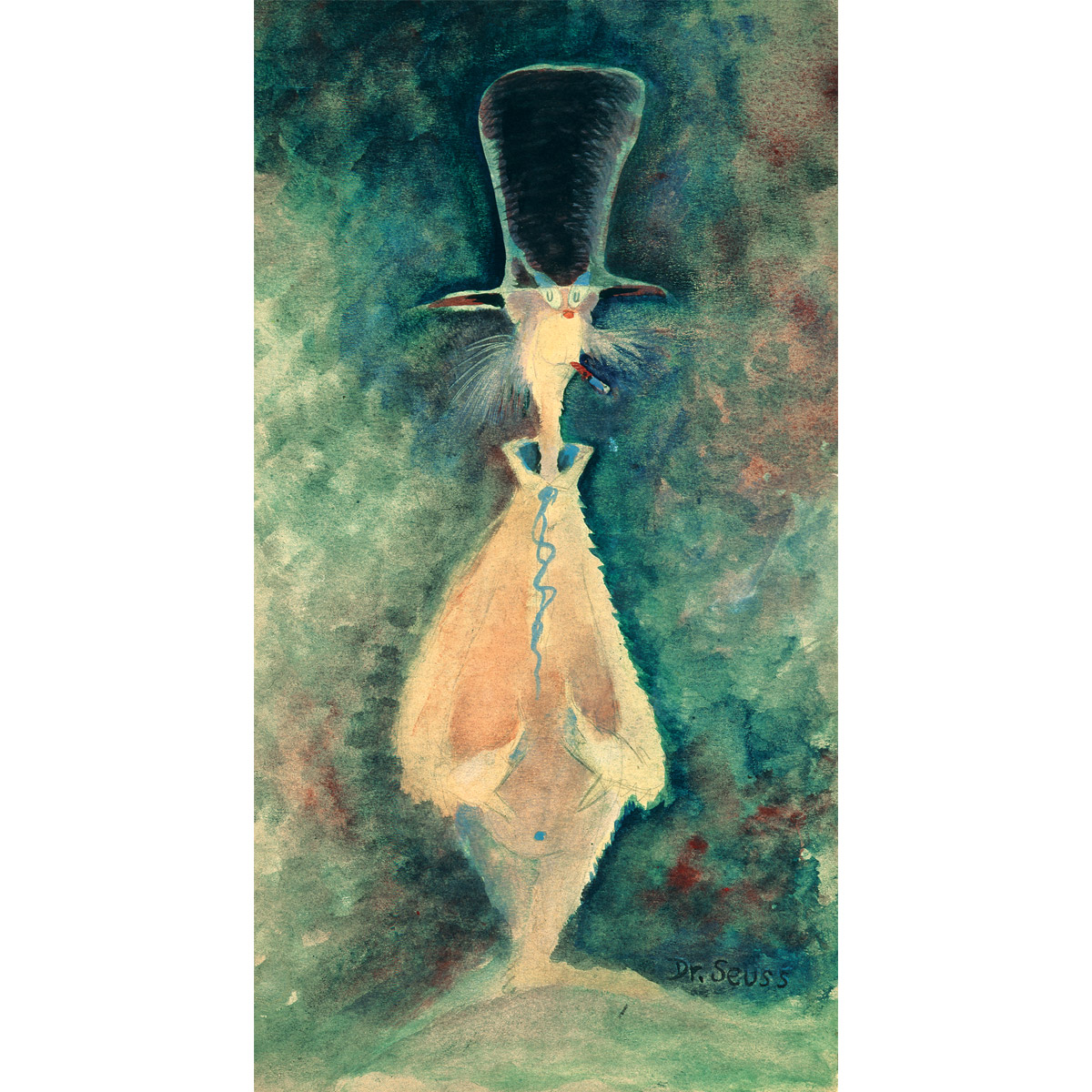

The most recent release from this collection, The Cat Behind the Hat, is the only self-portrait currently available—the other two are sold out. This iconic self-portrait ran in The Saturday Evening Post on July 6, 1957. Appearing just four months after the launch of The Cat in the Hat, this classic image depicts Dr. Seuss as his mischievous alter ego, complete with red and white stovepipe hat, cat ears, and the Cat’s now famous red bow tie.

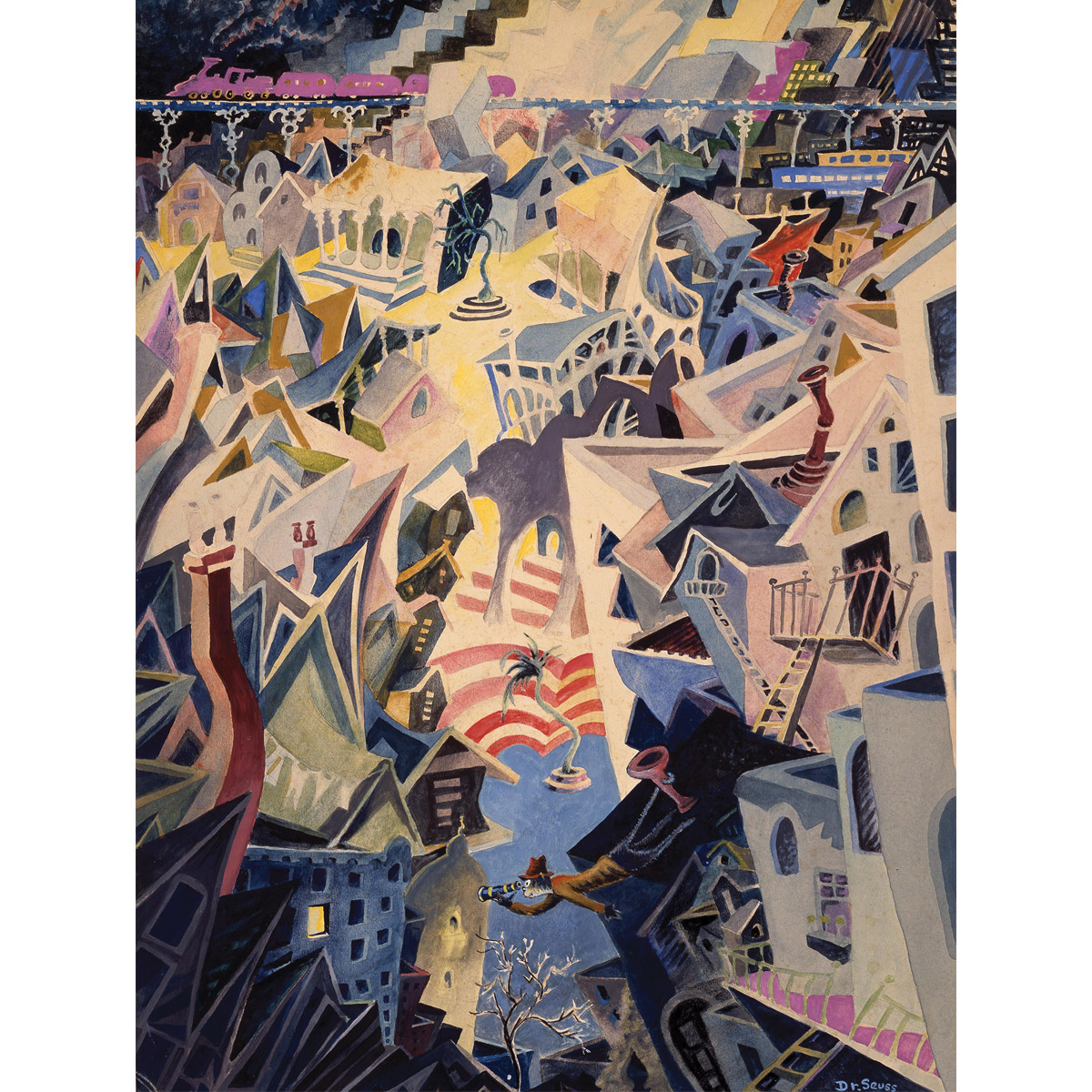

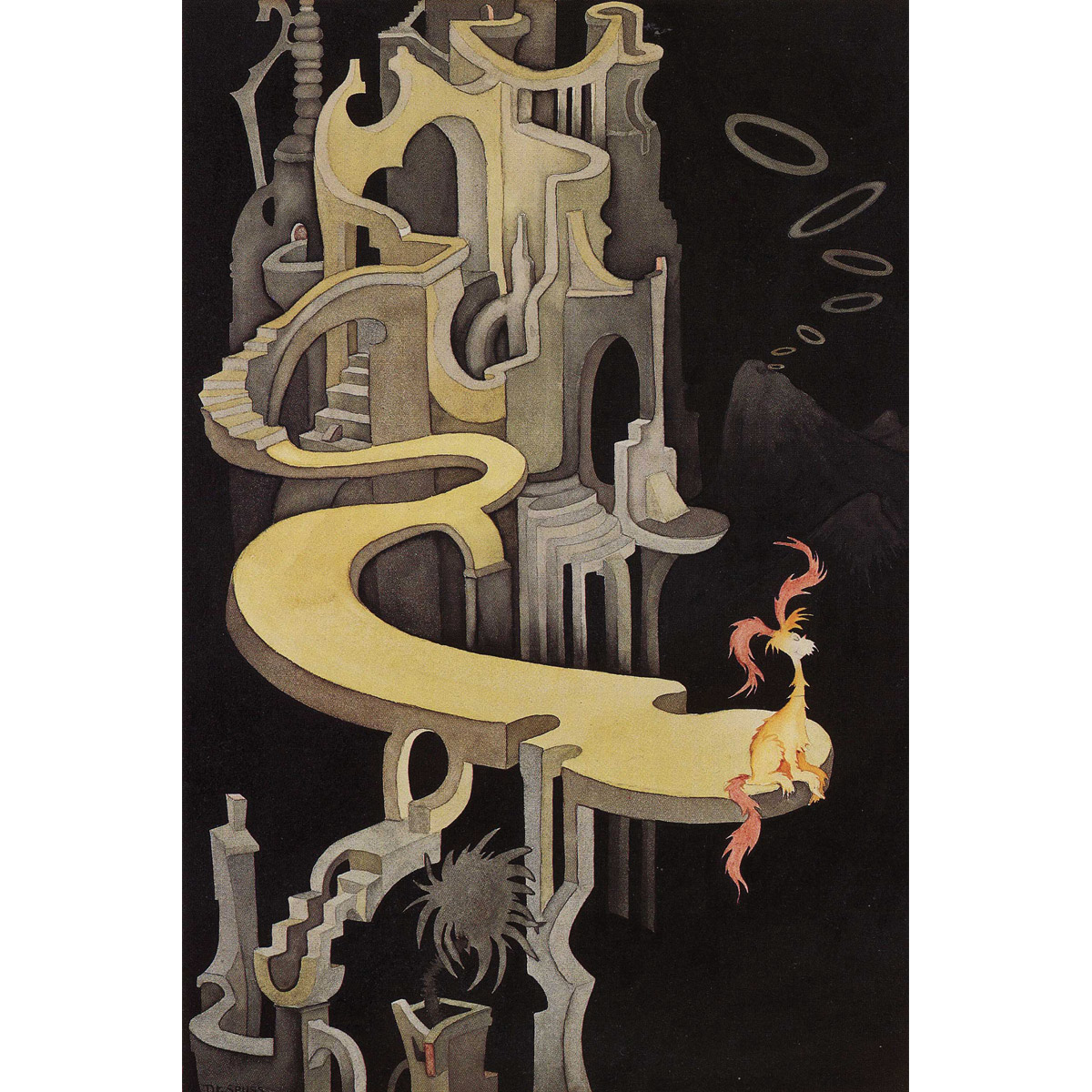

The Deco Period

The international design style art deco originated near the outset of World War I and remained popular through the end of World War II (circa 1915-1945). As this time frame fluctuated dramatically between years of want and plenty, art deco was an elegant, contemporary interpretation of the standards and expectations, fascinations and frivolities of each culture in which it developed. The paintings that Ted Geisel created during this period reflected that roller coaster of dreams and desires.

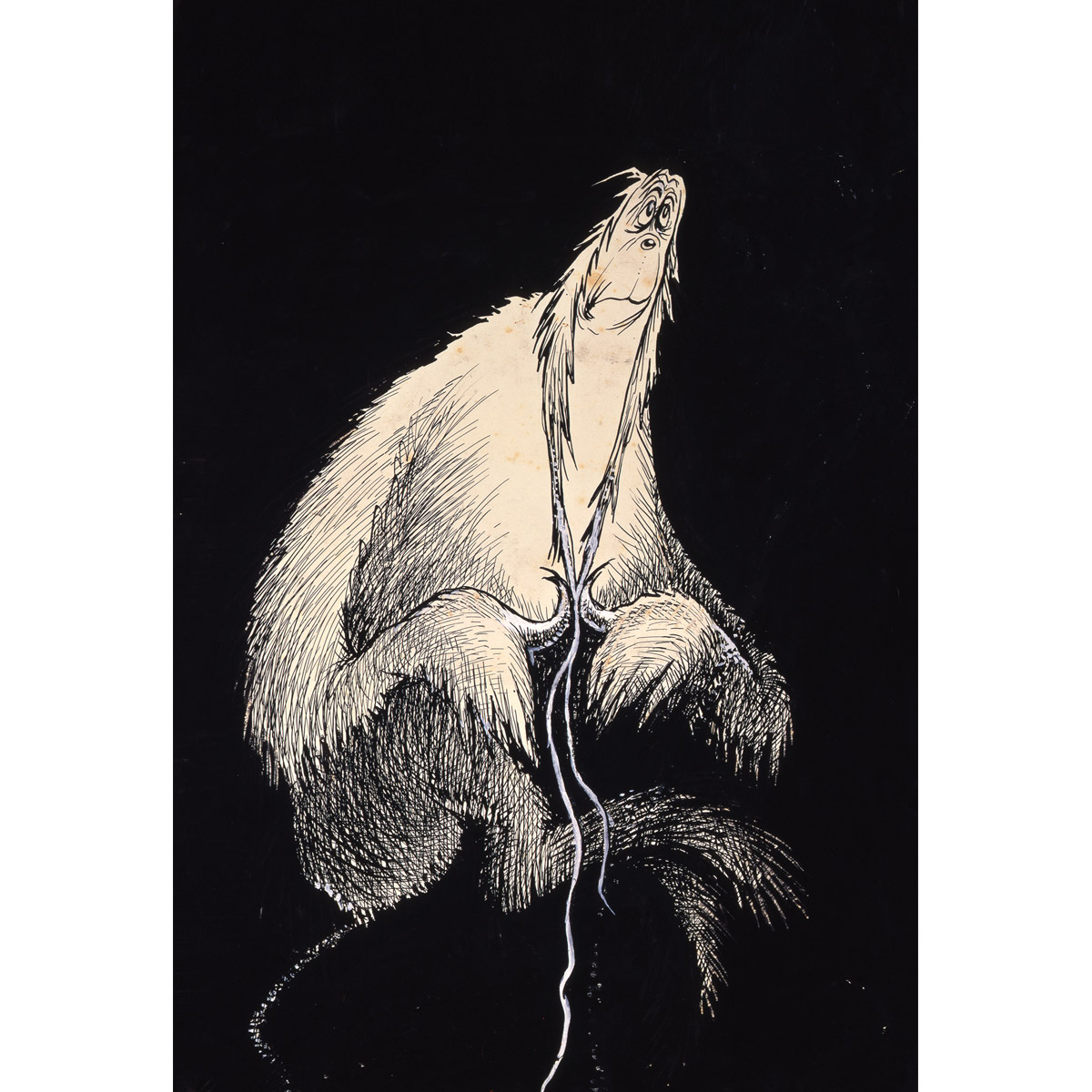

Many of Ted’s paintings of the 1930s and ’40s used an artistic element derived from his most successful work as a commercial illustrator. Referred to here as Geisel’s Deco Period, these years allude to his instinctive use of saturated black backgrounds combined with art deco elements often found within the architecture of his artworks. Ultimately, he created a new visual language that accentuated the muted pallets so characteristic of this period. From signature smoke rings billowing from Seussian mountaintops to architectural labyrinths decorating otherworldly landscapes, elements such as these reflected Ted Geisel’s creative interpretation of the art deco movement.

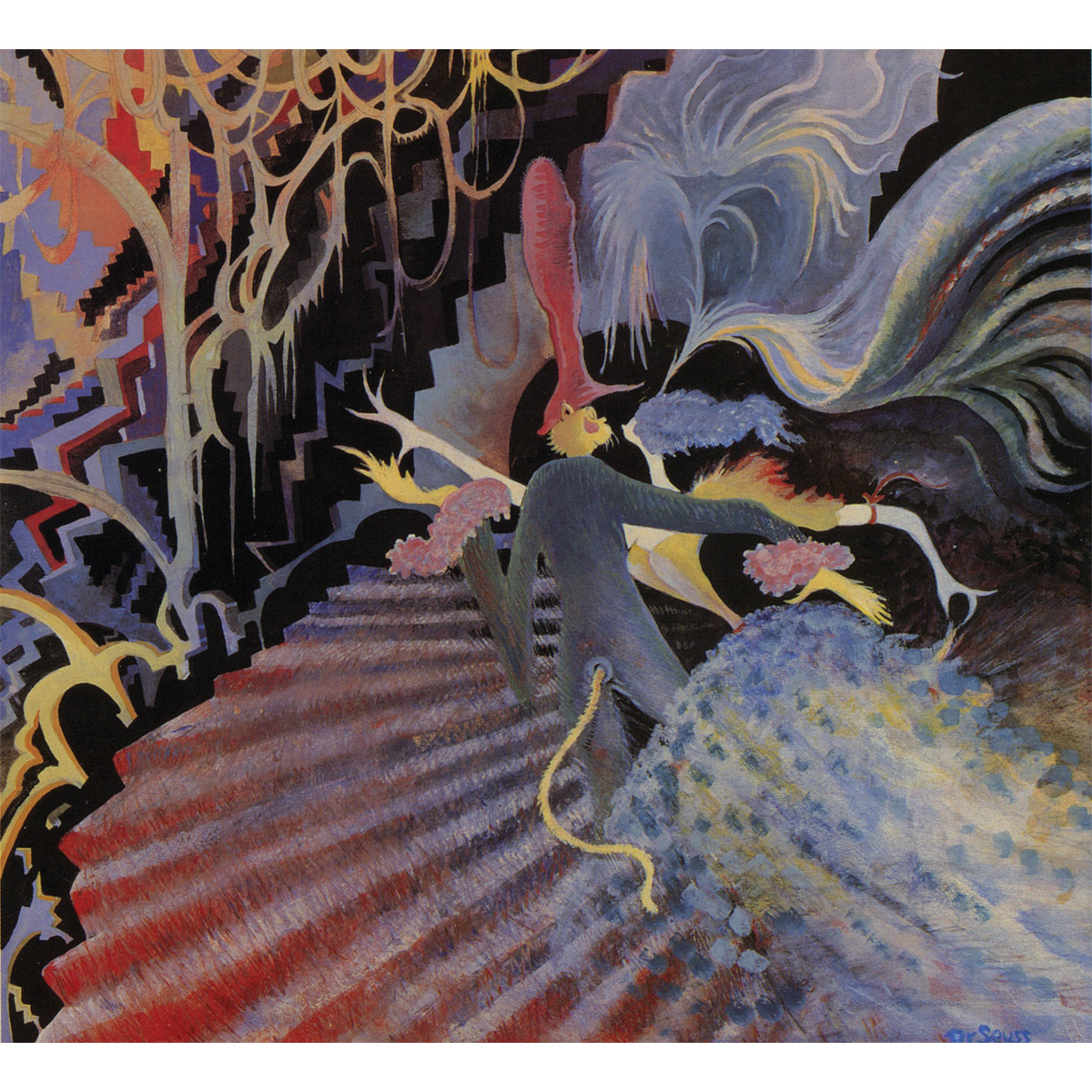

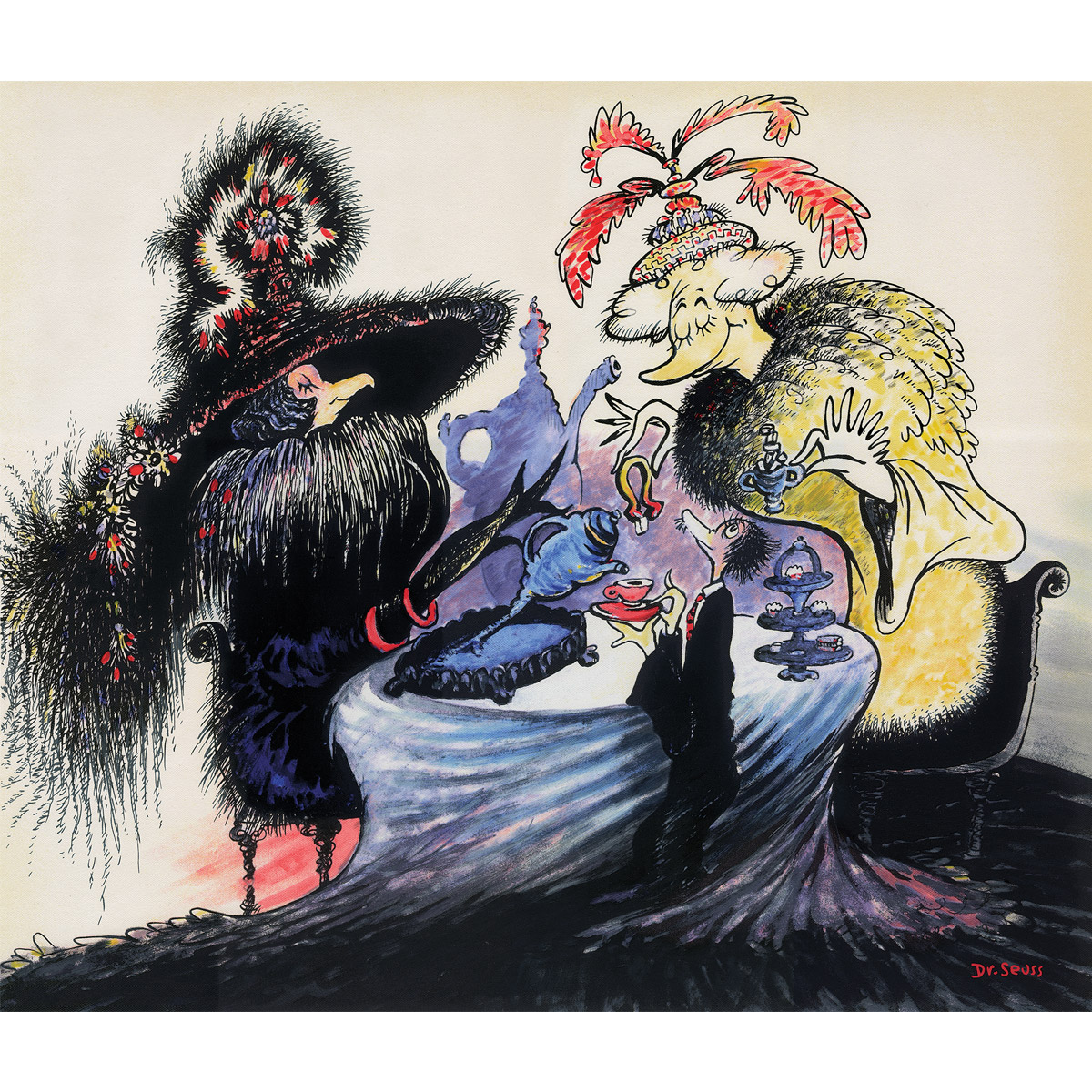

La Jolla Birdwomen

Ted Geisel fell in love with La Jolla on his first visit in 1928. Twenty years later, he began looking for a permanent California home—a place where the climate would allow him “to walk around outside in my pajamas.” In a one-day search, Ted purchased La Jolla’s Tower, a rundown observation structure atop Mount Soledad, which had become a lover’s-lane destination, its walls carved with the initials of hundreds of couples. Ted built his permanent home around the Tower, making it his studio.

Becoming enmeshed in the social comings and goings of La Jolla gave Ted a lush playground for concocting not only elaborate gags on his stylish neighbors but also for teasing them artistically. As one of the few men in town who worked from home, Ted lightheartedly considered himself a “bird watcher on the social scene,” always looking to create gentle spoofs of his chic female friends taken up in their whirl of luncheons, parties, and charity balls.

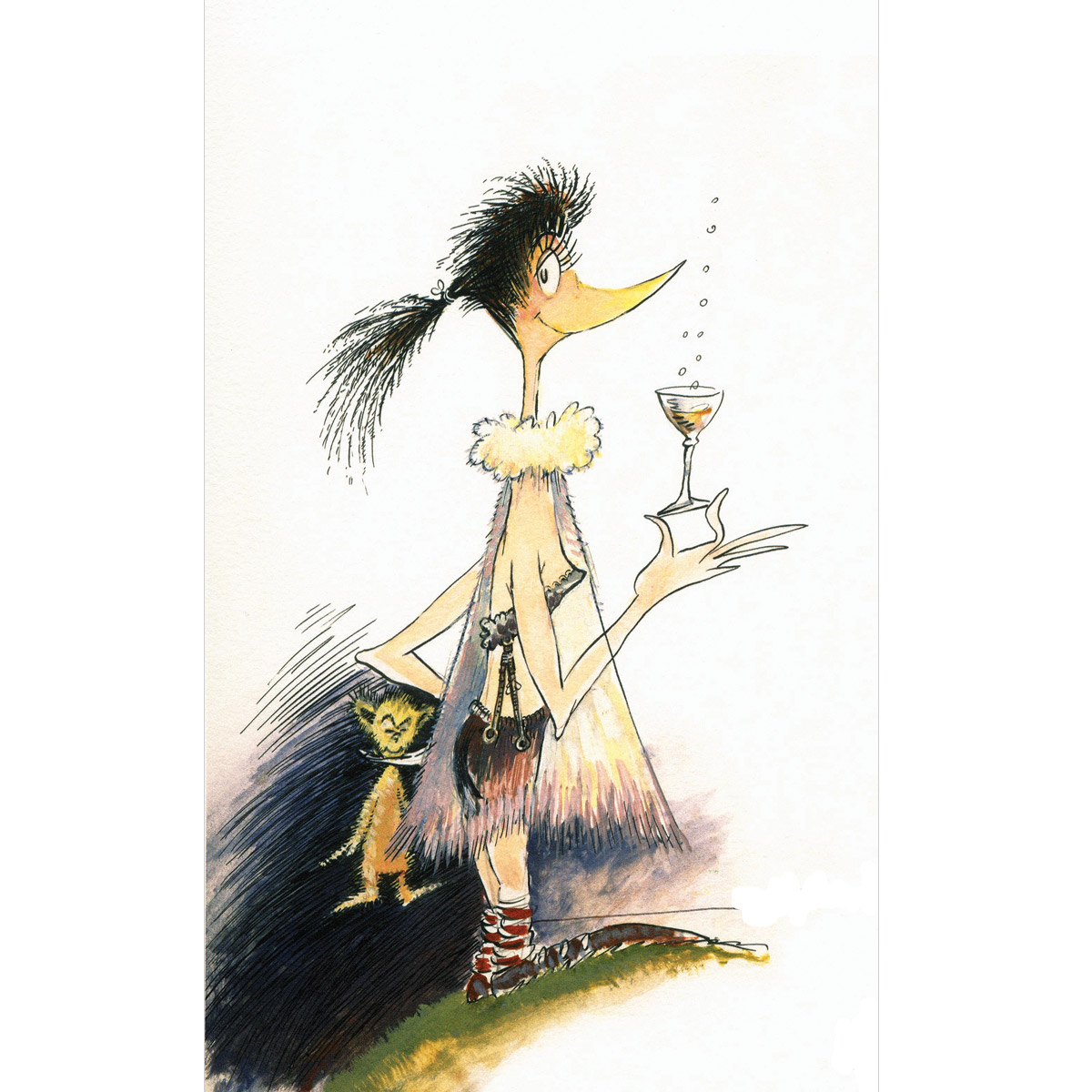

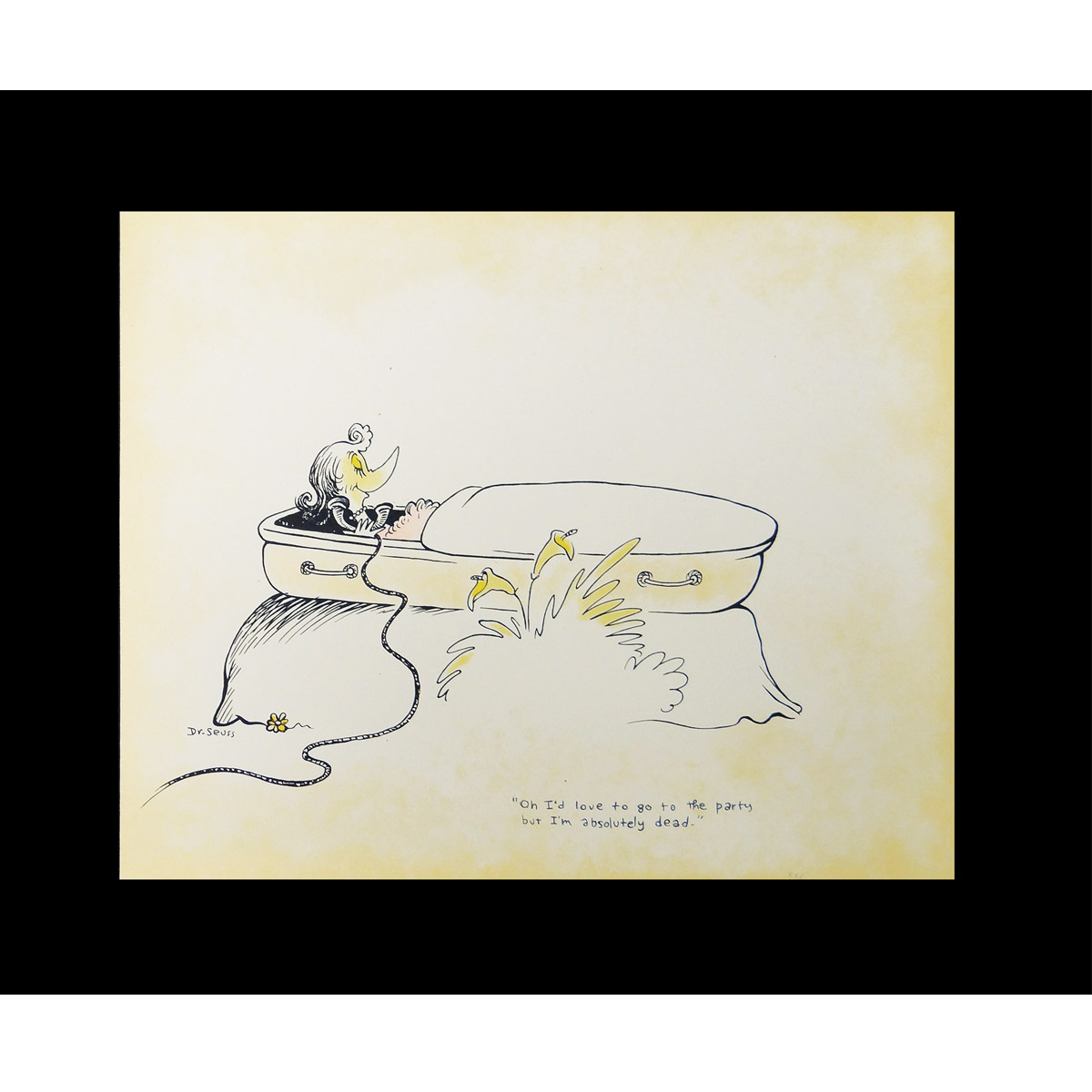

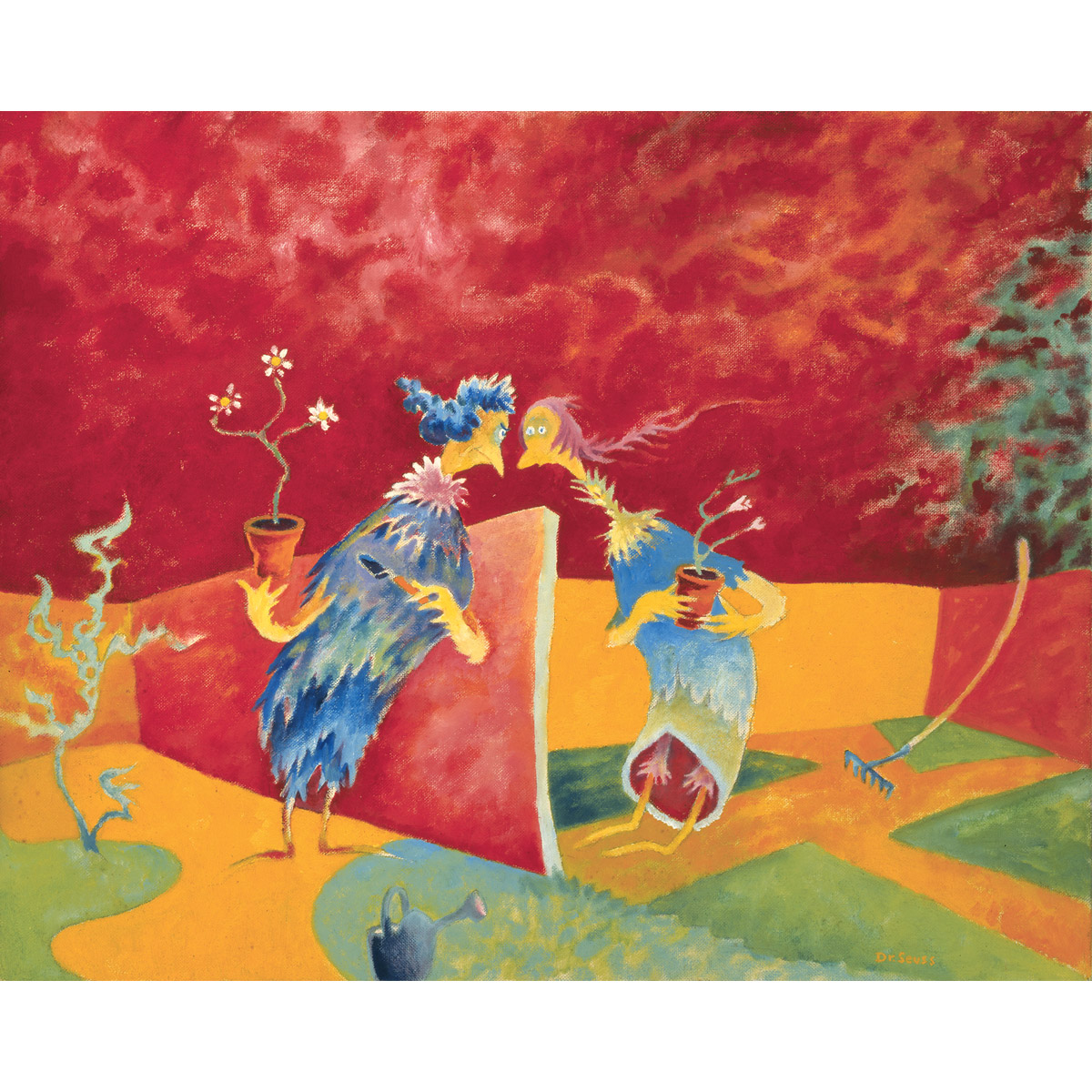

The result was the La Jolla Birdwomen series, a spicy collection of eleven known paintings with lyrical titles, works that could have sprung only from the mind of a genial witness—My Petunia Can Lick Your Geranium, Not Speaking, Martini Bird, Gosh! Do I Look as Old as All That!, View from a Window of a Rented Beach Cottage, and Oh I’d love to go to the party but I’m absolutely dead.

Anniversary Collection

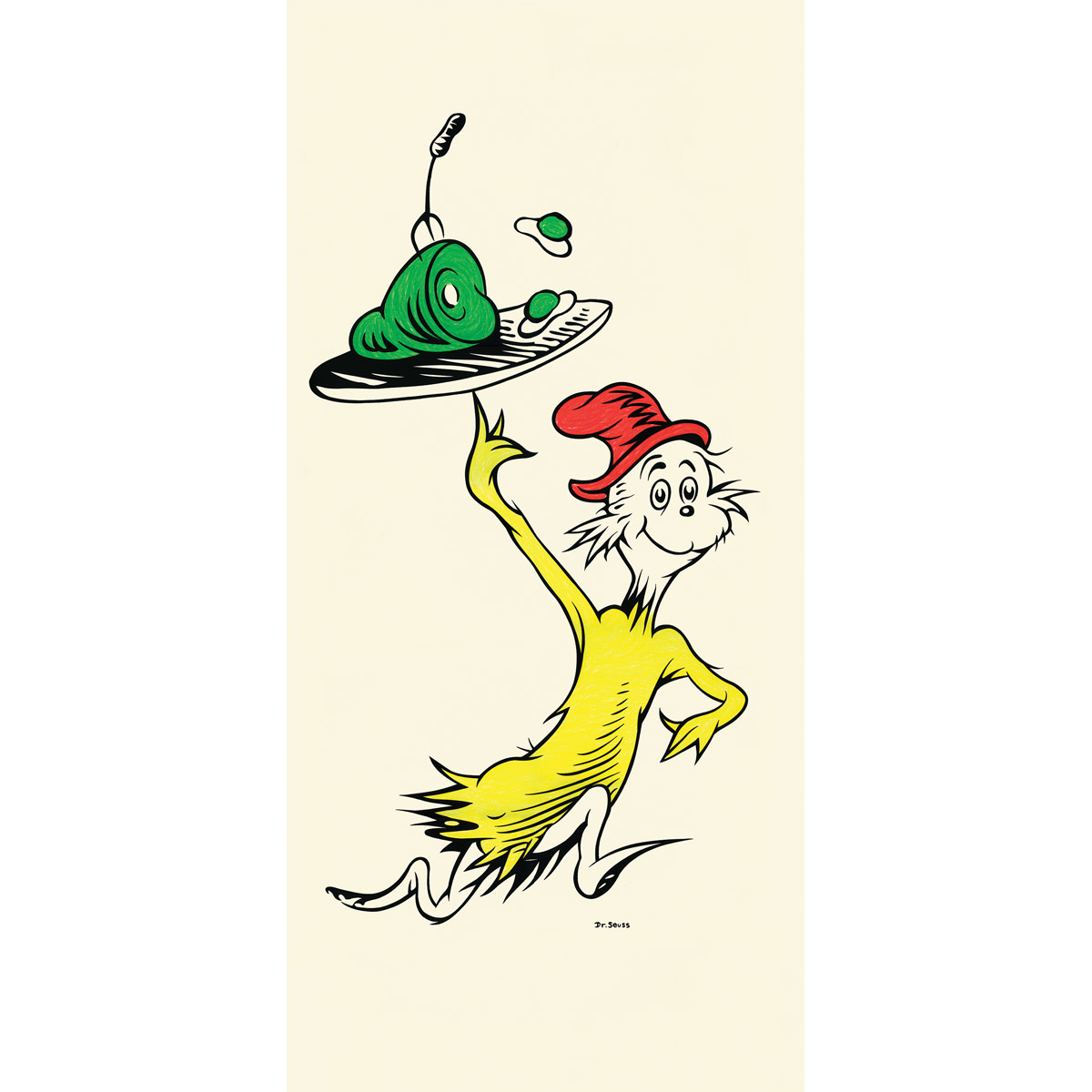

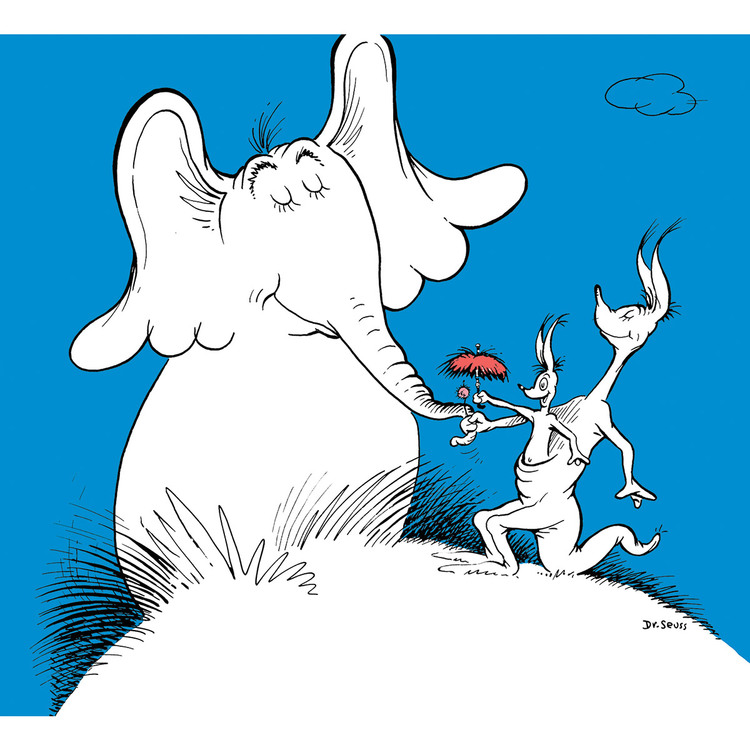

Special editions are published on the occasion of major milestones linked to Dr. Seuss’s most celebrated and important books or characters. These artworks are often presented in smaller edition sizes that traditionally sell out quickly.

The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins – 75th Anniversary

The Sneetches – 50th Anniversary

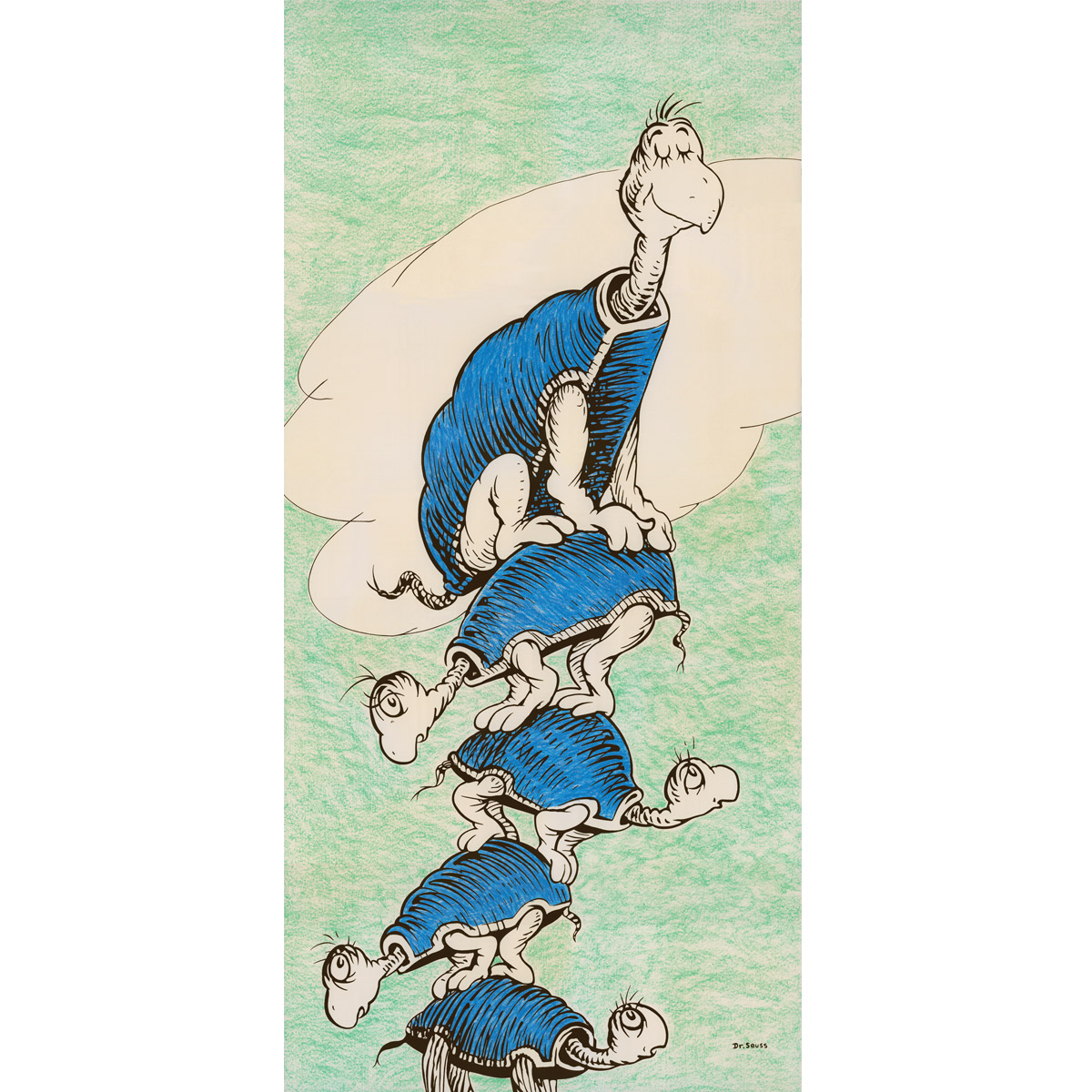

King of the Pond – Yertle the Turtle 50th Anniversary

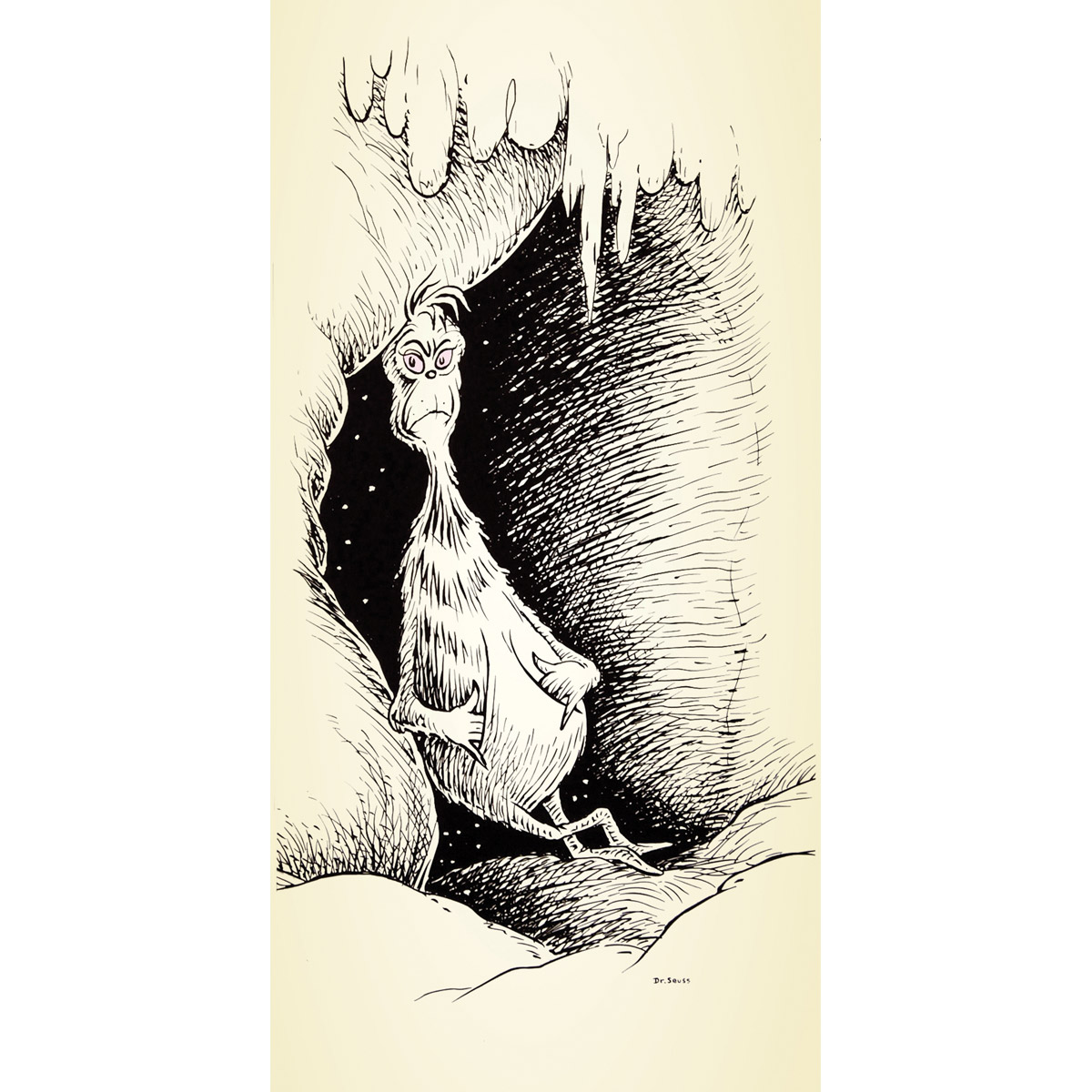

Grinch at Mt. Crumpit – 50th Anniversary (sold out)

Green Eggs and Ham – 50th Anniversary (sold out)

Ted’s Cat – 50th Anniversary (sold out)

Fox in Socks - 50th Anniversary

Horton - 60th Anniversary

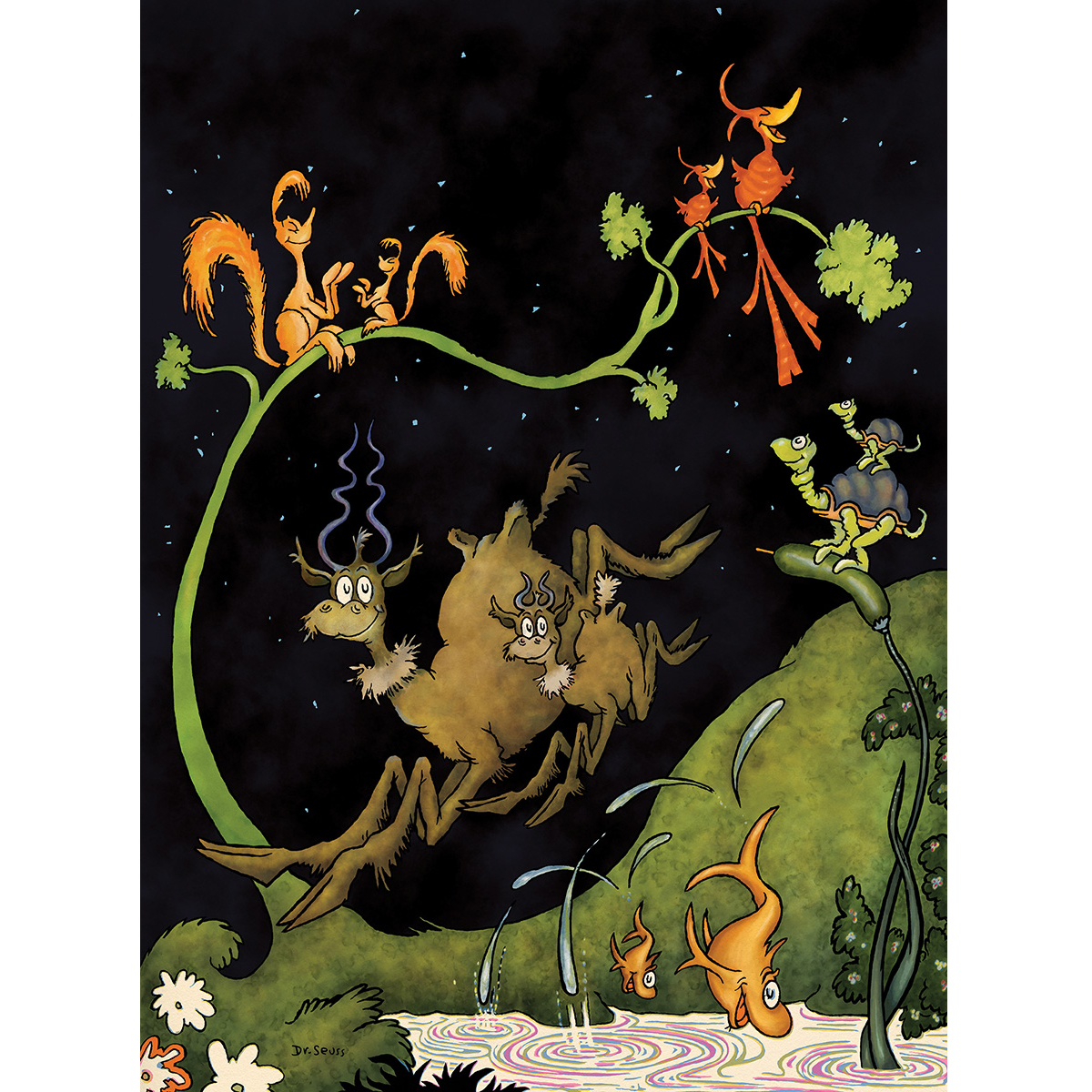

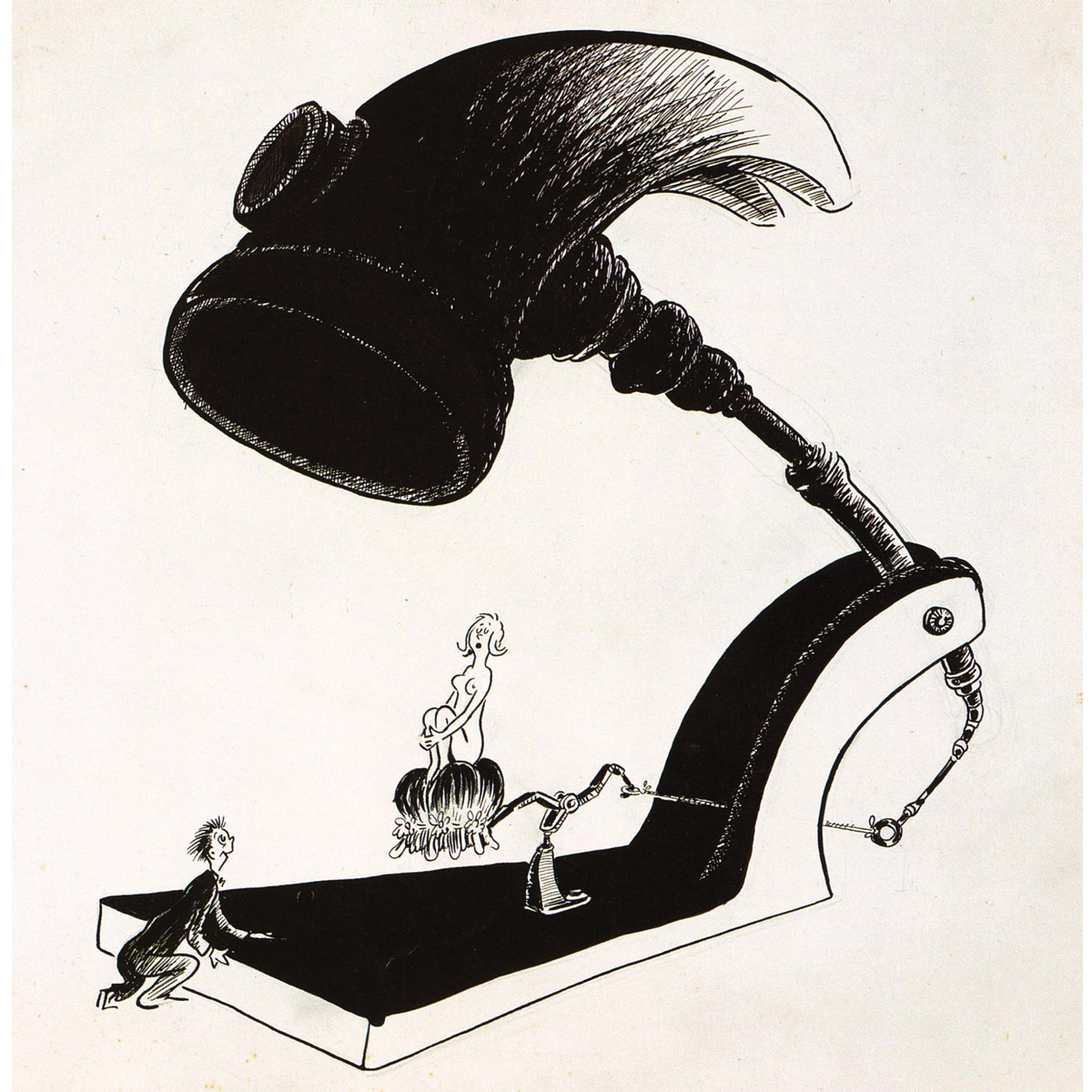

Pen and Ink

Drawing was innate for Ted. He doodled on notepads all the way through high school and college. During the hard-pressed early 1930s, Ted supported himself by selling cartoons to Life, College Humor, Vanity Fair, and Ballyhoo. In the early 1940s, the daily newspaper PM began publishing his editorial cartoons. By the time he was illustrating his children’s books, his deft final-line drawings seemed effortless.

One of the distinguishing elements of many of those early drawings was the use of saturated black India ink for the background, visually outlining and popping the imagery forward. This technique naturally carried over into Ted’s more sophisticated paintings. Like Norman Rockwell, Ted Geisel created every rough sketch, preliminary drawing, final line drawing, and finished work for each page of every project he illustrated.